| ICANN's Rod Beckstrom, left, met with President of Bulgaria Georgi Parvanov and First Lady Zorka Parvanova. Photo courtesy of the President of Bulgaria's office

Rod met with Georgi Parvanov, the President of Bulgaria, in December 2011. Here’s what Rod has to say about the meeting:

“It was very interesting to meet with the President and hear him talk about how important technology and openness are to him. Bulgaria has somehow managed to provide a very high bandwidth in the country at very low cost. Many of the consumers pay only $8 to $12 a month for high speed Internet access, and by high speed I mean two to three megabits per second and higher. So the president and the country have a very impressive commitment to that; and he talked about how it was a multi-year effort to accomplish this achievement for his country. He said it was a challenge politically as well.

Parvanov talked about his desire to further open up the educational system of Bulgaria to the world and very kindly invited me to give the inaugural speech at a new leadership institute that he and his wife created at the Bulgarian University for National and World Economy. The topic was Young Leaders and the Future of Internet Governance (click link for photos of the event). During our meeting, Parvanov also discussed how Bulgaria had been a center of personal computer technology in the Eastern Bloc before the fall of the wall and how, as a result, the country had a strong history of computer science . He said that was helping the nation now, and was valuable in helping a lot of the software companies and technology companies get going in Bulgaria.

I really enjoyed speaking at the University to about 60 young leaders from the leading business school in Bulgaria. I talked about the Internet, the future of the Internet, and Internet governance and technology. Like most young people in the U.S. they’re heavy users of cell phones, texting, and social networking. Most of them had Facebook accounts and were pretty active users and they had a strong interest in learning how technology could be used for different businesses in the future and in technology trends for the future.

Steve Jobs – Starfish or Spider?

Five months ago the world mourned the loss of one of the greatest innovators of all time: Apple founder Steve Jobs. Rod knew him, looked up to him as an iconic technology revolutionary, and witnessed both his idiosyncrasies and his brilliance. Rod’s memories follow.

I first met Steve Jobs in 1980 during my sophomore year at Stanford when I saw a flier announcing that the 26-year-old father of the PC would speak on campus. Steve was already world-famous when I showed up at Branner Hall with just a dozen other students to wait for him. Steve soon casually walked in and joined us. He had longish hair, wore blue jeans, well-worn beige suede boots and seemed like one of the coolest guys on the planet.

Steve sat cross-legged on the desk and talked about his dreams for computers and the future of technology.

PC’s were going to be everywhere in the world soon, he said, and would change our educational systems, societies and life. He talked about making computers everyone would want to have and promised that someday they would be as small as a book, foretelling the iPad to come some 29 years later. He dismissed the competition, talking about how primitive, clunky and overpriced he thought the IBM PC was and how Apple products were dramatically superior.

I had learned to write FORTRAN programs on punch cards for IBM mainframes and had just started to learn to code in Pascal. I had toyed with an Apple computer a few times but couldn’t afford to own one. I was amazed that the founder of Apple would chat informally with a dozen students about one of the biggest changes in the world.

I next met Steve in 1989 shortly after he founded NeXT computer. Then we started working with Steve and NeXT in 1992. I was running CATS Software Inc., a financial software company. We developed advanced derivative trading and risk management systems on the Sun Workstation. We helped Sun to land many of its first big global clients in finance like Merrill Lynch.

We had some incredibly creative and talented software developers at CATS. Soon they were talking about the amazing black NeXTcubes and the unique NeXTSTEP operating system. They were smitten with the incomparable object-oriented programming environment and development tools. We were working on a new financial engineering and trading platform that required visual programming where you could point and click to link components to create new financial instruments.

When our engineers saw the machine they really wanted to try it out, so I said, “Okay, go ahead and buy a few machines and two engineers can work on them for the next month. If it’s really so great, let’s see what you can develop.” The engineers took the bait. Our best engineers were soon falling in love with this machine because they could build applications on it that they could never even imagine building on any other platform.

At the time our company was caught in a technology chasm. Windows was just coming out but was still premature and unstable. Sun moved away from its NeWS desktop windowing interface and their X-windows technology was not catching on. We wanted to build primarily on the Windows platform in 1992, but decided it was not yet industry ready. It was going to need a number of years to stabilize and mature.

We were considering the Sun platform but had doubts about its desktop viability and limited interface tool kits. So we decided that NeXT was the right technology platform for building our next generation of trading systems. But it was a very new computer company with a thin market share. It didn’t compare to the likes of Sun, HP and IBM.

We thought Sun really needed the NeXT technology on its desktop machines. It seemed apparent Sun was going to lose the desktop workstation market to MicroSoft products, relegating Sun to the high-end server segment of the market.

So I talked to Scott McNealy, the Sun CEO whom I had known since 1987 and encouraged him to get the NeXTSTEP technology, telling him it ran on a Mach kernel which was based on Unix like Sun’s Solaris operating system. “Why don’t you talk to Steve Jobs and license NeXTSTEP?” I said. “If you do, then we’ll look at building some great new trading systems on top of it.”

Scott surprised me by being open to the idea. First he grilled me on why I thought the technology was so far superior to other platforms. Then he asked, “Do you think Steve will even talk to me about it?” I said, “Of course he’ll talk to you about it. Here’s his number. Why don’t you call him right now?”

So Scott called Steve while we were sitting in his office, saying, “Hey. I’m sitting here with Rod Beckstrom and he says that we should look at adding NeXTSTEP as an interface on top of our platform. Would you be willing to talk about it?” Steve agreed.

Six months later they announced OpenStep, which was going to be NeXTSTEP running on top of the Sun Solaris operating system. As an application developer, it was a dream come true—the best software development environment running on the most powerful workstations, a move that would get us out of the chasm.

After they announced the deal, Sun invested tens of millions of dollars to port NeXTSTEP to run on Solaris. I was hopeful that the best operating system and development platform in the world would soon become mainstream. We increased our software development program on the platform to millions of dollars per year. It allowed us to build some truly remarkable trading software.

During the first year, the Sun engineers made excellent progress. Then things started to change.

It seemed that NeXT started to withhold key new technologies that Sun would need to make OpenStep successful—key network drivers and other essential technology. The collaboration quickly broke down. It was almost as if Steve didn’t really want OpenStep to work—he just wanted money and the credibility of the partnership for NeXT.

The experience taught me how brilliant Steve was and also how incredibly difficult he could be, and how quick to break trust. It was all about what he wanted, on his terms, his rules, his conditions – all of which were subject to change at a moment’s notice.

Based on these disappointments, Sun switched its technology bet to the Java programming language, and the rest is history. Java became a dominant global programming language driving the development of the web and mobile apps.

We were devastated when Sun announced that it was discontinuing OpenStep investment. We had bet half of our R&D for three years on this amazing platform only to have Sun pull the rug out from under a critical new system. Losing the platform cost our company tens of millions of dollars in market value, and unfortunately, no other platform was mature enough to port to it at reasonable cost. So we had to abandon OpenStep even though some of the best and most sophisticated banks in the world had used the technology successfully. As a young CEO, I had to kill my own baby and abandon the product line. It hurt.

Things changed at NeXT too. Apple acquired NeXT and Steve returned as CEO and put the incredible NeXTSTEP technology into Mac OS 10, borrowing many pieces and components along the way. I never would have thought it would take almost 20 years for NeXTSTEP to become mainstream, but it did. It showed us Steve was brilliant, and difficult. Yet he turned Apple into the most financially successful company in the world.

So how can we analyze his management style? Was Steve more of a starfish or a spider?

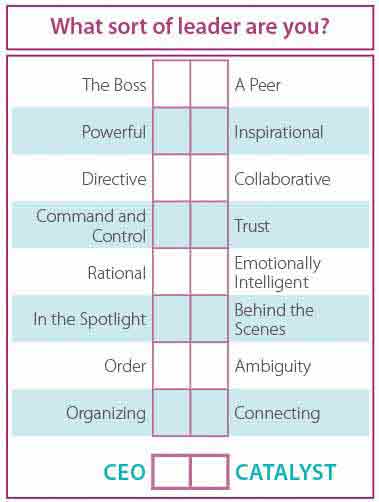

Let’s consider the criterion we mapped in the book to score Steve Jobs:

When I score Steve, I give him a checkmark in every box under CEO, with the only possible exception being in the “Inspirational” box on the right. He was both incredibly powerful and outrageously inspirational— pushing people beyond all normal limits to design and engineer remarkable breakthroughs.

So I would score Steve as a perfect “10” as a CEO as opposed to a Catalyst. He was about as top-down as you can get in Silicon Valley, although Larry Ellison might give him a run for his money, and Larry, in fact, was on Steve’s board.

So was Steve Jobs the closest thing Silicon Valley has to a “spider”-style leader? Perhaps. He ran Apple in a very top-down manner. He was involved in most if not all key design and engineering decisions. This drove some people crazy, but drove others to incredible heights of achievement.

As a CEO, he was a hardcore perfectionist who got exactly what he, not the group, wanted. Here’s an example. On one of my visits to the NeXT offices I used the men’s room. An employee told me, “Oh yeah. That’s the men’s room where Steve changed the color of the grout 17 times until he got the right color of gray.” I said, “You’re kidding,” and he said, “No. He had the grout and tiles taken out, and this whole thing redone 17 times until he got the right shade of gray. It was completely crazy.”

His perfectionism also came out when we attended an International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) Conference in Chicago. ISDA is the leading global derivatives finance trade association. Steve presented the breakthrough NeXT hardware and software technology. I followed, showing the CATS visually programmable trading system for derivatives built on NeXT. Afterwards, Steve said, “Hey, you did a really good presentation. The technology’s fantastic.” But he went on to say, “You’ve got to work on the interface. Your design is clean but the colors are not right.” Our graphics artists weren’t too happy, but he was right.

As we share in the book, centralized business models can be easier to monetize than decentralized ones, and this is what played out in the operating system wars. Apple has the most centralized strategy, firmly controlling both the software and the hardware of its products. Under Steve, Apple created closed platforms that were open to innovation, but only on Apple’s terms. In the 1980s and early 1990’s Apple lost enormous market share to Microsoft because Microsoft created a standard across everyone’s PC hardware while Apple chose to control the hardware and the software. Yet as time passed, many consumers and businesses valued the ease of use and reliability that came with an integrated hardware and software solution. Enough openness was added to bring in developers, such as for iPhone and IPad apps.

Over time, the market came Apple’s way because of the incredible breakthrough products that Steve and his team delivered. Out of hundreds of companies that tried to build new computing platforms, Apple won with its centralization. The company is now worth more than a half trillion dollars.

Microsoft has a hybrid strategy—it owns its own operating system (centralized), but allows others to build the PC hardware platforms and competes with others in applications (like MS Office). It is another stellar success and its value is roughly half of Apple’s.

Finally, true to the themes in the book, the Unix operating system, the most decentralized and open source operating system that runs hundreds of millions of computers in the world today, has generated through the variant Linux a $10 billion market cap for Red Hat Inc., the leading company providing support for the platform. Thus we see a higher market cap for the centralized models, but very high value for society from the others as well.

Steve was the computing Da Vinci of our time, part artist, part genius engineer, a revolutionary, an unbelievable designer, and an inspiration as well as a miscreant to many. He was not a simple man. In losing him, I now appreciate the unique experience I had, in some small way, to work with him. He was and will remain an enigma—one of a kind. A great spider-style CEO, he changed the world on his terms and had an impact on us all.

[Disclosure: Rod owns shares in both Apple and Microsoft]

Rod Interviews Gen. Stanley McChrystal

One of the highlights of Rod’s past few months was the following interview.

Stanley A. McChrystal is a retired four-star U.S. Army general . While serving as Commander of the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) from 2003 – 2008, he succeeded in taking down Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, leader of Al-Qaeda in Iraq. He last served as Commander, International Security Assistance Force, and Commander, U.S. Forces Afghanistan.

In this interview with Rod the General discusses how The Starfish and the Spider has affected thinking and decision making in the U.S. military. During the interview the General commented that while only some of the top military leaders had read the entire book, they understand the concepts and it is common to use the language of The Starfish and the Spider in discussions.

The General learned about the book from Tony Thomas, his Director of Operations (J3) at the JSOC. They saw the nature of the Taliban and al Qaeda networks as a decentralized phenomenon and were attempting to understand it. The book gave them the confidence to believe that a new way of looking at terrorist networks and organizing to fight them , was necessary. The book gave them much needed validation.

| Rod Beckstrom: |

I understand that you’ve started a leadership training program called CrossLead. Can you give some background information on what motivated you to start this program? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

With JSOC we operated on principles based on The Starfish & the Spider, but we never named the method. When I got out, we had to call it something so we named it Crosslead, because it crossed organizational lines and brought various elements together.

We came to the realization—through experience, not theory—that you have to spend a lot of time shaping your thoughts, processes, and your physical spaces to maximize the efficient use of time and the flow of information. Then individual decisions are pretty simple because they go into a context that is already built.

But we found that leadership in this environment is different. I found that the kind of leadership I had experienced and practiced when I was a junior officer just didn't fit the bill anymore. I no longer worked in a private office, but instead worked in an open situational awareness room or SOC which meant that I am transparent every waking hour. How I worked with people in that transparent environment, how I provided guidance, was different.

In some ways it was challenging, because you have to be a good leader 24 hours a day instead of just when you walk out of your office. Plus I was leading people I didn’t know. It was interesting and I'm sure you found the same thing at Homeland Security. When you have your own organization and you pay them, that's one group, but that's not really your team. The team is everybody in the community of interest or action that is required to make something work.

We had to work with the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) but they didn’t speak my language. They did not come from my culture, and did not necessarily understand my jokes.

When I commanded JSOC, I had to put together a group of teams, composed of very diverse groups that needed to align behind one common view of winning. Some of them were 30 years younger than me, and some of them were significantly older. Some of them came with institutional backgrounds and biases and sometimes limitations from their headquarters. I had to lead them through influences as opposed to command, because I wasn’t given command of this network; I was allowed to lead it. And that took a different kind of leadership, one of persuasion and influence. It wasn’t impossible, but it required a completely different approach. And not just for the senior leader, but all the leaders. For it to work, the whole organization has to agree to that.

So the idea of a CrossLead course for executives is first to teach them what CrossLead really is, because it’s definitely a change in your way of life. It’s a pretty significant change in the way your organization works; but it also means that the leaders themselves have got to make pretty significant changes in how they interact. So they’ve got to buy into this. They’ve really got to become committed to it or it just won’t be nearly as effective.

|

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

So is it fair to say that in some ways you’re trying to teach conventional hierarchal executives to be better catalysts, to be more catalyst- style leaders, to be more peers in working with others? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

That’s exactly right. |

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

What’s the hardest part of doing that? You’ve had to work on this with probably hundreds of thousands of people when you ran JSOC and the operations in Afghanistan and now you’re working with other people. What’s the challenge to helping people make that transition, if they want to? And how many people really want to make that transition? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

Not everybody does. A lot of people say they do, but when you actually show them what’s involved, it’s different. The hardest part is getting them to let go of the side of the pool, because typically people are in leadership positions because they’ve had a level of success. For the business world it might be financial success. So changing the way you are after you’ve been successful is hard for individuals, and it’s hard for companies.

We work with one company that has been very successful, but came to the very impressive self-realization that they weren’t going to continue to be effective unless they changed dramatically. Their president was in our most recent leadership course, and he brought 11 of his senior people and led them through the whole course. He’s one of these guys who completely understand that they’ve got to change the way they operate. You don’t always find that kind of transformational leader who can say, “Okay, here’s what we’ve got to be.” Because, again, it’s uncomfortable to be part of the change yourself.

We want to be the expert that’s directing change in our organization because we’re already masters of it, but what we find in this case is the leader is really learning and changing along with the organization. And that can be less comforting to some leaders than others.

|

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

How do you think leaders can become more self-aware or get feedback on how they’re doing in that transformation, assuming they do want to change and become catalyst style leaders, or cross leaders as you might call them? How do they get the feedback? How do they get some objective sense of whether they’re making progress in opening up and changing? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

We try to help them have interactions with other leaders at various levels in a way that allows them to see interactions occurring. They get feedback from other leaders. And of course you’ve got to empower more junior people to feel comfortable providing the feedback. You’ve got to increase interactions. We believe a lot of people hate video teleconferences, but we think for geographically dispersed organizations, they can be magic if they’re done right.

We haven’t done it yet, but we’re very interested in trying to explore how we could measure objective metrics on things like information flow in an organization. For instance, it could be helpful to determine just where your emails are going. Maybe not include all the content, but just to gain a sense of how much blood is flowing through the body. I think that would actually be instructive. |

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

Get a map or graph of the email flow of the network connections? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

Yes, and be able to show if they are stimulating the flow of information effectively, and see if they could improve on this. |

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

You’ve said that it took roughly a couple of years to move the JSOC and the operations in Afghanistan towards a sweet spot, towards what felt to you more like the right balance between top- down and heavily decentralized and delegated. The US military is a magnificently large and complex organization. When you look across the whole organization, where do you see the balance being, and how do you think it needs to move, and in which direction, towards a sweet spot? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

It has a long way to go. The problem with the large size of the military, or any other large organization, is that there are so many entrenched habits and cultures and bureaucracies that exert pressure towards the status quo. Because when you move the organization towards a decentralized structure, with a catalyst style of leadership, there’s a certain amount of vulnerability when your information is out there. You see wiki leaks. Wiki leaks have caused many people to say, “Aha, we can’t share information anymore, now that these wiki leaks occurred.”

You see pressure like that occur and suddenly people want to go back to a more conservative mode where they share less and interact less, because it’s less risky personally. And for organizations it can reduce risk as well. The problem is that when acting out of fear you can’t succeed as a whole. We have to succeed as a whole. For instance, look at the politics now of the recent budget deal where you have the Democrats and the Republicans attempt a budget compromise. They were unable to come up with a compromise, yet they both know the ship will sink without one.

It’s unbelievable to watch from afar, because it’s so obvious, and even they know it. A tremendous number of organizations do that in a less dramatic manner. That’s sort of what happened to the U.S. Intel community before 9/11. This kind of thing happens on a daily basis, although there have been improvements.

|

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

What kind of material would you like to see added to the Starfish and Spider book that might help leaders learn how to be better catalysts or transform their organizations? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

That’s a great question. It would probably be material focused on what the leader has to do. Because I think you captured very well how the organization can change, including the leader’s role. But it’s much harder than it sounds. In the spider model, the leader is there and although if the organization loses a “leg” it can die, the comfort level you get from knowing that this is how things have always been done is reassuring.

Working in the starfish model, I found as a leader it was often uncharted territory. I had different relationships with people. I had to set up different structures and procedures that made me feel confident that we were going in the right direction. I would like to see more details in your book about how a leader operates.

And the other thing I found is that the work of a catalyst style leader never ends. The problem with running a starfish-like organization is that the leader—and not just that individual, but the entire role of leadership in keeping the energy of the starfish model in place—is constant. I used to refer to this as spinning a pie plate on top of a wooden stick. As soon as you walk away from it, things will decay pretty quickly.

You can’t just send a memo and say we’re going to do this and then walk away. You have to be constantly breathing energy into it. Addressing these issues more fully would be very helpful, in my view, and could also help people gain confidence they could actually do it.

|

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

When you look at training leaders as you’re doing now through CrossLead and as you’ve done under your leadership of JSOC, are there any generational differences or issues that come up? Is the younger generation better at picking some of this up? Or are some of the older generation better because they’ve got so much experience and they’ve always been learning? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

Yes, I’ve found that the younger generation embraces it much more easily. Part of that is generational, but part of it is where they are in their organizations. If you’re a young person in an organization, you don’t feel the same cultural limitations of your organization that you might 20 years later if you’ve got a family, three kids, and you really need the job. So I think it’s not all just generational. I think it’s also where you fit. You’re hanging a lot out if you’re a middle manager in an Intel community and you’re sharing information that traditionally you didn't. |

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

I’ve heard, by the way, that you may have a new book deal, is that right? Is there anything that you can share on that? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

Sure. I’m writing my memoirs, but they are going to be very focused on leadership. In fact, the part that you and I are discussing now is the part I’m trying to capture with as much clarity as I can. Because I think I was part of this pretty amazing change process. I certainly wasn’t the only person who drove it, but I was there for it and I experienced it, and I’m trying to capture how we went through it, what it meant to us, what it meant on the battlefield, what it means for the future, and that sort of thing. |

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

It sounds like you really started to figure out how decentralized the Taliban and Al Qaeda were in 2003, and discovered how JSCO had to change its operations – which in some ways, of course had been quite decentralized. Looking back over your career, what might you have done differently if you’d learned these things earlier? And what’s your advice to young people starting their careers now in the military or in the private sector? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

That’s a very good question I ask myself. I think that you spend the first part of your career developing your tactical and technical expertise and your standing inside your organization. You become very good at whatever it is you do but you also become fairly insular. It wasn’t until later in my career that I realized that wasn’t nearly enough to be successful. You really need to develop an understanding of what other people do, and how you deal with them, and how you reach out and leverage.

So my advice to the younger officer would be to seek a better understanding of different potential players, and that includes inter agencies, other services, and foreign countries. Consider the importance of learning foreign languages and things like that. I think people who expand their understanding of how things work are going to be the most valuable players in the future. These will be the people who can reach out and pull teams together.

|

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

In a recent interview the new chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Dempsey, said that The Starfish and the Spider was on his reading list—one of the three books on his nightstand. How many other people in the military leadership do you think have been exposed to the book or talk about the books and the concepts? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

I think it’s one of those things where you can make the literary allusion and most people will know what you’re talking about. I’m not sure if all have read more than just a summary, but some have. And then to be very honest, there are a lot of people who would say, yep, they’ve read it, nod up and down, and say they’re a starfish, but in reality they absolutely run a spider organization. |

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

That’s so true. It just amazes me. Some people I talk to talk say what starfish they are, and they’re the biggest spiders crawling around. |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

And yet they could pass a lie detector test thinking they are--that’s the amazing thing. |

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

So how are you developing your business? Tell me about how CrossLead fits in to what else you’re doing, to the suite of activity that’s keeping you busy now. |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

I’m doing a range of things. I’m teaching leadership at Yale, which I just love. I don’t use the CrossLead word, but it’s historical leadership and I enjoy that. I’m doing some public speaking and I talk about leadership. I’m writing the book, and I want it to be a serious history book and a leadership book, not a “who I like and don’t like.” It’s not going to be one of those.

And then we’ve started a business called the McChrystal Group. The CEO is actually a Navy Seal who I worked with, and now he and I are co-founders. But it’s all based on leadership. We offer a leadership course, we do leadership consulting with other firms, and it’s all centered around preaching the gospel of CrossLead, which in many ways is the gospel of The Starfish and the Spider.

We really have this passion about changing the fact that Americans aren’t leading very well now. That’s true in business, but it’s also true in government and in other areas as well, and we really think we’ve got to change, because times have changed. The old ways just aren’t very effective any more.

|

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

Absolutely. Is this Jon Iadonisi, the former Seal, who you’re referring to or is it someone else you’re partnering with? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

Jon’s in the crowd, and he’s in our offices as well. He and Tim Newberry are partnering with us. Their company, White Canvas Group, produces some very creative technologies, some of which we use. But my co-founder was Dave Silverman. Our group actually includes three Seals, four old A rmy Rangers, some ladies that we’ve worked with at other times, and then we’ve hired some young people as well. We want tiered levels of perspectives. |

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

Is most of your practice right now targeted at the private sector, at corporations? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

It has been completely thus far. We wanted to avoid the perception that we’re old military guys acting as military contractors. We’re really interested in the private sector, and hopefully that’s where we’ll be able to do most of our work. |

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

That’s excellent. So if you look at where the United States is headed now, with its activities in Afghanistan, trying to pull out, trying to hand it over to the locals, do you think that’s too fast, too soon, or should a larger investment be made over a longer period of time before that can be accomplished? Or do you think we’re on the right track? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

I think decision makers in the U.S, Afghanistan, and Pakistan have all made a lot of mistakes, and we’re now in a tough position for everyone. There’s no winner out there right now, because it was incredibly difficult and people had made many mistakes.

Not all actions and decisions were mistakes, but there’ve been many. I do think the region is important. I’m not sure that we need to automatically say we’re going to keep this many forces there to do this, because in reality the Afghans are just about at the point where they can and must do it themselves. It has to be their solution. But I am hopeful that we’ll develop the idea of a strategic partnership.

After 1989 when we basically pulled out of the region after the Soviets left, Afghanistan went through a really hard period, and I think that we paid a price. We, the world, paid a price for disengaging. I don’t think you can disengage in the world any more. I don’t believe in traveling around the world with 100,000 man armies. I do think that we can downsize a lot, but I personally hope we’ll stay committed, because confidence is what they need. They need confidence more than they need stuff right now.

|

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

Yes. And that brings up their leader. How do you feel about Karzai as a leader of Afghanistan? What’s his style between, say, a starfish and a spider? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

That’s pretty interesting, because when viewed from the West, he’s a president, a term we’re familiar with, and he’s elected, but his style is actually based upon the reality of politics in Afghanistan, and he has to be a combination of a king and a political leader. He has to deal with tribes and pull together different constituencies. So to be effective his role must be this combination of different approaches, all of which look a little bit difficult for us to completely comprehend.

Now he has a tough time with it, I’m not saying that he’s got it licked by any means. But an American president doesn’t typically have to deal with a tribal leader or deal with things like that in the same way President Karzai has to. So I think that we could do a better job of understanding his situation, and I think he could do a better job of understanding how his country fits in relationship to the rest of the world as well.

I was just out there last week and spent a couple days with him and he wants to be a great partner of the United States, but it’s been a tortured relationship. It’s one of those situations where I think every bit of time and effort we put into building relationships and understanding is going to pay off.

|

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

Interesting. Have you recommended the Starfish book to him by any chance? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

I haven’t, but I should. He would actually understand it, because Afghan centralized leaders have never had the kind of real power to be a spider. The Bonn Agreement set up a situation with a very centralized central government, but Afghanistan’s never had that reality. So the people in the provinces could relate to the starfish concept, and they would view the head of the spider in the center of the starfish as being a real head, not a false one—not hugely powerful, able to influence and motivate, but not direct. |

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

Another thing I’m curious about is, to what extent did you discuss and share these strategic concepts on starfish and spider decentralization with Gen. David Petraeus, who of course is a sociologist by his training and background, and really worked hard to decentralize certainly the war in Iraq. |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

We talked an awful lot about this, because he and I have known each other for 30 plus years. So as he watched us operate, it was interesting. I stole some techniques from him and then he took the techniques that JSOC developed and implemented many of them across the force. He became one of our biggest proponents, and that was hugely valuable. We have slightly different styles, but share some very similar underlying principles. |

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

Let’s come back for a moment to the Taliban itself. I really enjoyed reading your excellent article in Foreign Policy, “ It Takes a Network.” You talk about how you had to build a network to fight the Taliban network. Can you talk about the Taliban network and how you have seen it evolving over these past eight years? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

The Taliban is an interesting crowd because they started as a fairly ideologically motivated group in 1994 when they came out of Pakistan. The idea was sort of “throw the bums out” and they were very popular when they first did that. But when they became a government, they became ideologically so extreme that it was ridiculous.

In the last few years of fighting them I discovered that they do have this central leadership that operates out of the Quetta Shura (the top organizational leadership structure of the Afghan Taliban) and they give general guidance. They don’t have a tremendous amount of trust internal to their organization. So they tend to operate a little bit more independently in some areas. They do appoint shadow governors and they do all these kinds of things, but they’re not hugely coordinated.

However they do leverage several principles very effectively. They leverage the idea that the government is a public government, they leverage the presence of foreigners, and they leverage the idea that the West is as corrupt. Beyond that, they mostly leverage the idea that the government of Afghanistan is corrupt, and that’s true. And so that part resonates, and then they leverage the fact they carry guns.

So they’re not an impressive organization and if they transitioned again into governance, they would actually fail. It would be an utter disaster, worse than last time, and the Afghan people sense that. But they’re still a force to be reckoned with because some of the things they’re against do resonate with people. They also have a coercive ability.

|

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

How do you look at the Taliban network as being different than the Al-Qaeda network? |

| |

|

| Gen. McChrystal: |

Al-Qaeda is much more structured but elastic, it’s a flexibly structured organization. Al-Qaeda is much more connected by tight links between certain key people. They don’t have as much local control anywhere, although there is local franchising in areas. Al-Qaeda is a much more extreme bunch of characters. And of course they’re in many areas. Their ranks are pretty thin now.

Al-Qaeda is an idea that’s about to die, because its rationale will go away. As soon as the Arab Spring showed that, for better or for worse, Muslims are going to determine their own fate, then the raison d'être for Al-Qaeda doesn’t resonate.

|

| |

|

| Rod Beckstrom: |

Well, General, thank you very much. It’s been a great honor to speak with you. |

For more information on General McChrystal’s CrossLead training program visit http://www.mcchrystalgroup.com/crosslead.php

Back to top

Maria Sipka's Column

Assetless Billion Dollar Enterprises

How long did it take Conrad Hilton to build a multi-billion dollar hotel empire? What about Walter L. Jacobs, who founded what is now known as the Hertz Corporation? And department stores such as Saks Fifth Avenue, Barneys New York, Lord & Taylor, Nordstrom, Von Maur and Bloomingdale's where women flock to buy their fancy dresses?

It took decades to build these powerhouses that, to this day control a decent share of the retail spending. And to have successfully built these corporations, you needed access to exorbitant capital, influential connections in politics, business & society and a team of well-paid executives. A kid out of college wouldn’t contemplate achieving this level of success until now.

What’s happened in the last five years is changing how consumers behave and spend their hard- earned and borrowed cash. A billion people are engaging actively on the social web building friendships, sharing photos, videos, thoughts, comments, reviews and practically their entire life. Facebook and twitter expose this data that ultimately feeds some college kid’s idea of transforming how we live, breathe and sleep on this planet. It’s at this point that the social web becomes truly decentralized and we see the most disruptive and useful services emerge.

Airbnb transforms the accommodation market, matching people with a place for those looking for a place to stay. Founded in 2008, the company is now worth over US$1 billion . Airbnb has over 100,000 listings in 16,000 cities and 186 countries. Listings include private rooms, entire apartments, castles, boats, manors, tree houses, tipis, igloos, private islands and other properties. Unlike Hilton, the company does not own one property and its only overhead is the building, managing and marketing of their technology platform and brand.

GetAround enables people to rent another person’s car nearby – a social car sharing service. No check-in counter. No costly insurance. The company doesn’t own one car. The idea is that car owners invest huge amounts of time and money into an asset they barely use. Cars are driven only 8% of the time, while potential drivers walk past block after block of underutilized cars. GetAround connect the dots... to help people get around. A similar service, Zipcar, that actually owns its cars, raised $174 million in its IPO in April 2011, giving the company a valuation in excess of $1 billion.

And 99dresses, a soon-to-be-released fashion swapping marketplace started by a Sydney teenager gives women an infinite wardrobe in which they never have to wear the same dress twice for a fraction of the price of buying them.

These peer-to-peer driven service platforms are rapidly, in a matter of months, taking on the giants of yesteryear with little experience, almost no capital, network or star-studded team. It’s the combination of a brilliant idea at the right time and the ability to execute with minimal resources that offers consumers the opportunity to stay in a cozy home, or drive to a magical location wearing a gorgeous dress all courtesy of the person down the road.

Maria Sipka is the CEO and founder of Linqia – an online marketplace helping companies identify, connect and engage with masses of highly targeted consumers participating in online communities and groups. Follow Maria on twitter or contact her on LinkedIn.

Back to top

Starfish Principles At Work

Brady Capital Research

Barbara Gray started Brady Capital Research in January 2011 after more than 10 years in her successful career as a sell-side equity analyst. She had decided to take some time off to focus on her personal life and start a family. She named her company after her baby boy, Brady, who is the model in the image above.

Here is Barbara’s story:

I still clearly remember going through The Starfish and The Spider back in January 2008 with my highlighter searching for insights into the fate of Yellow Pages. Four years ago, most investors were still steadfast in the long-held belief that directory companies were a source of predictable and sustainable cash flow, resulting in a superior business profile. But I was not your typical follow- the- herd Sell-Side Equity Analyst. Back in September 2006, I incurred the wrath of a few corporate clients that I classified as “Straw houses at risk of collapsing” in my controversial research report titled: “If The Economic Wolf Comes Knocking, Is Your Trust Built of Bricks or Straw?”

And having used Craigslist to find my last place to live, and from my ongoing conversations about how technology was disrupting traditional business models with my boyfriend (who I am happy to report is now my husband and business partner), I knew I could no longer be in denial. It was Rod and Ori’s book that really crystalized it for me and gave me the conviction to go against the consensus and downgrade Yellow Pages to SELL:

“We believe investors may be naively assuming directory companies will be able to simply shift their advertising clients from print to online and maintain their current high level of free cash flow. However, we believe the 2006 business book, The Starfish and the Spider, provides a note of caution and a dose of reality. According to the authors, “starfish” organizations, such as Napster (NAPS-NASDAQ), Craigslist, or Wikipedia, which rely on the power of peer relationships, are causing an increasing threat to traditional “spider” organizations, which have weaved their webs over long periods of time, slowly amassing resources and becoming more centralized...We believe one of the authors’ key principles of decentralization: as industries become decentralized, overall profits decrease, provides a note of caution for directory companies.”

“Yellow Pages No Longer a Conservative Investment: Downgrading to SELL” – Barbara Gray, CFA –Analyst, Consumer/Diversified, Blackmont Capital – January 4, 2008 (YLO.UN-TSX-C$13.98)

Today, four years later, Yellow Pages’ stock is trading in the pennies.

“Ideology is the fuel that drives the decentralized organization” Ori Brafman & @RodBeckstrom book “Starfish & Spider” http://ow.ly/8e5HD

Tweet from @barbcfa – January 4, 2012

If you click on the link in the tweet I sent out on January 4th, it takes you to the profile page for The Starfish and The Spider in the “Leading Edge” business book category in the Library of Brady Capital Research. As a testament to the valuable connecting power of Twitter, a true starfish platform, Rod saw my tweet and tweeted back to me the same day inquiring about how I fund my equity research group. As it is hard to explain that in only 140 characters, we carried the conversation over to e-mail. It’s funny, as I had not really thought about the costs involved with starting up my own investment research platform.

Two years ago, I decided to take time off from my 15-year career in Sell-Side Research to focus on my personal life. And if you go to the home page of Brady Capital Research, you will see a picture of Brady, our now one-year- old baby boy. As being able to stay at home with Brady during his first year was priceless to me, it has not seemed like much of an opportunity cost to have not “worked” the past two years. And if you look at the extensive list of business strategy books in the library, you will see that a large portion of our “start-up capital” went to Amazon.com as I used the time off as an opportunity to indulge my passion of reading business strategy books, like The Starfish and The Spider. It is interesting as after Rod contacted me, I went back and reviewed the book and I realized how our firm, Brady Capital Research, has a very starfish-like DNA.

Looking through the ten “New Rules of the Game” in Rod’s book, I realized that we possess many starfish-like traits. “Diseconomies of Scale” (Rule 1) definitely applies to us as my husband designed our website using WordPress and I work in the mornings out of a local coffee shop taking advantage of free Wi-Fi. I think of it as my version of Cheers, except I arrive there at 6 am, not 6 pm, and order a Strawberry Tea Latte instead of a beer. And I try to conduct most of my calls on Skype, the starfish platform that has completely disrupted the telecommunications industry. To position our firm to be able to take advantage of the network effect (Rule 2), I am using starfish platforms such as Twitter and LinkedIn to build bonding, bridging, and linking social capital.

I think one of the most meaningful starfish traits we embody is “ideology is the fuel” (Rule 8) as our mission illustrates: “To create an innovative qualitative-oriented investment research platform focused on companies with a greater purpose.” Our ultimate goal to, “build a community connecting investors with heart and soul companies and leading-edge business strategists and develop new ways for investors to look at and value companies” is based on my realization that all of my best calls as an Analyst have come from insights that I have gained from reading business strategy books.

For instance, my best LONG call was when I initiated coverage on lululemon athletica (LULU-NASDAQ) on September 11, 2007, shortly after its IPO, with a BUY recommendation. Based on our investment thesis the company had created a unique “blue ocean strategy” and was positioned for superior sustainable earnings growth.

Part of our conviction also came from the parallels we saw between lululemon and Starbucks after reading “Pour Your Heart Into It: How Starbucks Built a Company One Cup at a Time” in which Howard Schultz, CEO of Starbucks, shared, “O ur goal was to build a great company – one that stood for something – one that valued the authenticity of its product and the power of its passion.” Interestingly, our idea is based on the theory that the “best knowledge is often at the fringe of the organization” (Rule 4) and our ability to build a community rests on the notion that “everyone wants to contribute” (Rule 5).

The challenge we face is that most investors don’t care whether or not a company has a “greater purpose” as they believe the doctrine that companies should be focused solely on maximizing value for shareholders at the expense of their other stakeholders. And they continue to use traditional quantitative analytical and valuation metrics and dismiss our qualitative heart- and- soul versus shell investment thesis.

As evidenced by the fact that Time’s Person of the Year for 2011 was “The Protestor,” social media is ushering in the era of the Social Revolution. And we believe social media is the “catalyst” (Rule 7) that will change the rules of the game, as we expect it will quickly erode the traditional economic moats of “shell” companies whose competitive advantage is based on their ability to exploit their stakeholder base.

At the same time, we believe it will foster in a new source of competitive advantage for “heart and soul” companies whose business strategy is focused on building higher levels of social capital for their stakeholders. In the end, I believe what will ultimately differentiate us from other investment research firms is the “Power of Chaos” (Rule 3) as Brady Capital Research is really just an incubator for our innovative, yet potentially very disruptive, investment thesis that the “Social Capital Revolution will change companies’ risk/growth profiles and accelerate the value erosion/creation process.”

Visit Brady Capital Research for more information.

Share Your Starfish Story

Thomas Barnett on Wikistrat

Thomas Barnett, the Chief Analyst of Wikistrat shares this story about how his company applies starfish principles to strategic thinking and planning. Tom answered the following questions to explain what they do at Wikistrat:

Q: As Chief Analyst, can you provide a brief overview for our Starfish Report readers of what Wikistrat is, and how it works?

A: Wikistrat is the world’s first crowd-sourced consultancy. We leverage a global community of several hundred strategic thinkers to tackle simulations of likely international events and unfolding global trends, the war-gaming of future conflict or crisis scenarios, and strategic planning exercises – all for private- and public-sector clients. To make such an offering possible, Wikistrat has put in the time and effort to not only create and nurture our global community that welcomes talent from all regions and a diverse range of subject domains, we’ve built – and continue to expand with each simulation – an online model of globalization itself in a wiki-based, scenario-driven format. So we’re basically three things at once:

1) Facebook for strategists from around the world who are looking for a place to improve their skills, run with others of their own kind in a 21st-century guild environment, and come together for paying consulting engagements;

2) Wikipedia-like global intelligence exchange (our globalization model, or GLOMOD); and

3) Massively multiplayer online consultancy (MMOC) that offers clients a crowdsourcing alternative to the usual “butts-in-seats” consulting firms that can’t possibly match our price points when it comes to massed brainpower because our overhead costs are so minimal.

We’re convinced that this is the future of consulting in the globalization era because our approach allows clients a far more interactive engagement (e.g., they can participate in our simulations on a real-time basis), combined with a wisdom-of-the-crowd dynamic that effectively addresses today’s complexity and constantly morphing international landscape. Our simulations can run for hours, days or weeks – even months. They can be mounted at very short notice and generate actionable insights for clients from the minute we turn them on.

Q: To what degree does Wikistrat embrace a decentralized “starfish” style of leadership? Is there a centralized leadership system that oversees and directs Wikistrat’s network of analysts?

A: Wikistrat is starfish-like on a number of levels.

First, we assemble temporary teams for client engagements, just like a production company that is formed to make a movie and is then disbanded. So there’s no set pattern of who gets pulled into any one engagement.

Once we establish the core group of senior experts needed for the task, we send out invitations across the community to fill out the remainder of the participant pool, aiming for the highest diversity possible by subject domain, region, and experience level, and then we see who takes up the offer and runs with that opportunity.

I can’t tell you what a typical Wikistrat team looks like, because we don’t know until it comes together in response to the client’s request. Our job is simply to keep the global “bench” deep and wide and accessible in a real-time fashion, understanding – of course – that we vet everybody before letting him or her into the community. We aim for a very particular “crowd.”

Second, our guild-like community self-organizes itself to an unusual degree. We’ve set up subject-matter and regional desks and assign analysts to those based on the interests they express in their applications and intake interviews. But once inside the community, they’re pretty much free to pick and choose the bulk of their activities, which leads to a lot of pleasant surprises as people develop talents and display skills you wouldn’t expect, based on reading their resumes.

Over time, that’ll lead to new desks being formed in response to the self-initiated clustering of minds. We’ve also “gamified” the community for the younger, less-experienced analysts, which means we offer them a variety of pathways to earn points that elevate their network standing and consulting opportunities over time, while “sharpening the blade” – as it were.

So far, these younger analysts have gobbled up those activities and constantly push us to generate more (like the world’s first crowd-sourced strategy book), which is an awesome responsibility for Wikistrat, because we’re filling a gap in their professional training and thus empowering the next generation of grand strategists that this world desperately needs.

Third, the GLOMOD itself is self-organizing. We like to say at Wikistrat that, “analysts don’t compete, they collaborate by making scenarios compete.” When analysts work on client engagements, or in one of our internal training simulations, or even just when they working the GLOMOD on their own – for their professional gratification, if they disagree with or can’t bear the analysis on some scenario page, they’re free to “take their fight outside,” as I like to say, by creating an alternative scenario page on the wiki.

That means the GLOMOD grows from the inside out, but in directions no one can predict. Ideas cluster on their own, creating new centers of analytic gravity within the GLOMOD. My job as de facto chief architect is to make sure no branch grows so long that it’s unsustainable or unduly isolated in its reasoning, meaning we want other portions of the GLOMOD to reach out and establish analytic linkages – in both a figurative and literal (i.e., HTML) sense. Thus the GLOMOD is really a collective-but-distributed “brain” that grows according to the dictates of the community working in response to client requests.

Fourth, we have no set sales staff. Our analysts themselves are our primary sales force. Wherever they go and whatever they encounter in their various other professional endeavors, they’re empowered to market Wikistrat’s services – that crowd-sourced alternative they can’t deliver themselves. That means they can propose new offerings and solicit new clients on their own, which, once we accommodate them, lead to Wikistrat’s growth as a consultancy and company.

The same is true on recruiting, as our analysts are our primary recruiters.

With offices in New York, Tel Aviv and Sidney, Wikistrat is effectively headquartered in the “cloud.” To date, our central staff remains quite small – as in, single digits. We’re going to try and keep it as small as possible going forward, but we’re facing a significant challenge in that regard, due to the growing demand for our services and the sheer fact that analysts are signing themselves into the community from around the world every day. But these are good problems.

Q: What happens during live multi-player simulations?

Typically analysts will spend about half of a simulation working out – meaning populating with rich detail – alternate scenario pathways, exploring them across what we call a Scenario Dynamics Grid, or a generic multi-stage breakdown of a scenario’s lifespan, however long that may be (i.e., anywhere from hours to decades, depending on the client’s time focus).

Then the analysts will vote on the most plausible and/or revealing – to the client, that is – master narratives, which are the sequencing of individual scenarios at various stages in however many combinations make the most sense. Once we have those in hand, participants will often analyze how these various master narratives impact the interests of the most relevant real-world actors – in effect assuming their personas. At that point, our crowd will start brainstorming and then competing various policy options for those same actors.

That’s a fairly generic client engagement that involves simulating some possible future event. But we can vary the structure of simulations by any number of variables, and clients can always follow up with requests for additional modules (e.g., inserting a “shock” into an unfolding scenario to test some policy option).

In this regard, one of our favorite schemes is having multiple groups of analysts play the same real-world actor – say a nation-state government (in truth, analysts often spontaneously organize themselves along these lines in simulations whether we tell them to or not). Another is to have actual citizens (analysts) play their own countries. Too many American exercises simply have Americans playing everybody, when what you really want is Chinese playing Chinese, Indians playing Indians, etc. That’s where our global community comes into play. That’s how you obtain truly new sets of eyes.

And that’s really the underlying principle we follow in all design – “collaborative competition” of descriptions, concepts, options, etc. So we like to compare the work dynamic to additive manufacturing – aka, 3-D printing. We’re not aiming for the destructive, subtractive dynamics of the blogosphere, where everyone spends way too much time tearing down each other’s ideas. We want our analysis to be built, layer by layer, with as many hands shaping the intellectual product as possible but with everyone getting credit for every single keystroke – all of which is instantly archived for the client’s access. Wikistrat is completely transparent in that way, which we think is hugely important in terms of making the client smarter – not just the analysts working inside traditional consulting’s “black box.”

One final thing to note from the analysts’ perspective: the “crowd” we source on any simulation works – on an individual basis – according to their own schedules. Our simulations have to go 24-7 because we’re global from day one. So we don’t ask our crowd to assemble in one room somewhere on the planet, thus allowing us to tap their wisdom in whatever natural context they currently reside – wherever they reside.

That means we get analysts’ best work because they offer their time at their greatest convenience. That’s why we prefer longer-run simulations for maximum flexibility, but if the client wants things faster, we accommodate that desire simply by increasing the size of the “crowd” to ensure a critical mass is achieved in a tighter time space.

Q: The Wikistrat site states that, “Wikistrat uses its patent-pending, digitalized, war-gaming methodology for engaging clients…” Can you explain how war-gaming methodology is used to provide geopolitical strategic analysis?

A: Besides the description I’ve already offered above, the key thing that differentiates Wikistrat is our simulations/war-games/etc. aren’t pre-scripted affairs that force analysts into either “fighting the scenario” (i.e., disputing its plausibility or fidelity to real life) or chaffing within its artificial confines. Because our whole methodology revolves around the wiki, our motto is, “Don’t fight the scenario, fracture it.”

Here’s what I mean: Wikipedia has one entry for me, and it’s so conflicted that the organization labels it “not up to standards.” The simple truth is, my thinking is controversial enough in several realms so that there’s no one set worldwide opinion as to its validity – go figure! In Wikipedia, that leads to a sub-optimal or less-informing outcome.

But in a Wikistrat simulation, we don’t try to contain analysts and their ideas within a single scenario. Again, if there’s a fight, we instruct the aggressor to “take it out” . . . on a new wiki page that thereupon competes with the “low fidelity” page that he or she cannot abide. So long as analysts are willing to put their money where their mouths are, and stand by the alternative scenarios they generate by providing accompanying policy options, then all we’ve done with that conflict is exploit it to the client’s benefit.

We can do all this because our exercises never commit themselves to paper or the responsibility – and cost – of massing several dozen experts in some resort hotel for X days, all of which creates massive organizational pressures on the game convener to go as scripted as possible so as to avoid wasting already sunken costs. Since we’re in the “cloud” from start to finish, the costs involved with accommodating out-of-the-box thinking is virtually zero. To me, that’s “starfish” because circumstances and creativity dictate form and function – not the other way around.

As for the “patent-pending” part, that’s our using the wiki in “competitive collaboration.” Wikipedia doesn’t compete its entries but Wikistrat competes everything. Throughout our war-games, analysts will vote on darn near everything. Clients can too. So our sims are intellectually invasive (i.e., “engaging”), but tremendously cost- effective due to digitalization.

Great example: L ast June we held an International Grand Strategy Competition with three-dozen teams of grad students from top universities from all over the world. We gamified it with a prize and had various teams assume the personas of various great powers. But to make it truly competitive and collaborative at the same time, in most instances we were able to get three different schools playing the same country. What that meant was that the three teams playing Pakistan competed fiercely with each other to be the best Pakistan, but they also fed off each other’s creativity. So the harder they competed, the more they collaborated. And you know what? This collection of teams truly turned my head around on Pakistan, taking me places strategically that I hadn’t considered.

Frankly, that’s why we use next-generation strategists in every sim we run. They simply don’t know what questions they’re not supposed to ask, and that makes them dangerously creative in everything they do – again, to the client’s benefit. If you fear “black swans,” nobody hunts them down better than those fresh minds that haven’t already been “made up.” Put some “young Turks” on a wiki burdened by too much conventional wisdom, and they’re like bulls in a china shop.

Q: As the author of three books based on your background as an analyst for the US military, you advocate for a new direction the military can take towards the globalization of peace. Do you think this can be accomplished within the military’s current top-down hierarchical leadership style? Do you think the military could/should engage civilian peace-oriented networks to achieve the goal of global peace?

My System Administrator “force,” or one focused on everything but big wars, was always based on the notion that it’s essentially a military-civilian interface function that tilts decidedly to the latter over the course of its operations. In effect, my SysAdmin force is a way for the military to transition – as quickly and as comprehensively as possible – the low-end policing, nation-building, frontier integrating, etc., to non-military actors (NGOs, PVOs, international bodies, private sector enterprises, local governmental entities, and so on).

It was designed to be “starfish” from the get-go; I just didn’t have that particular vernacular in my tool-kit at the time. Now, of course, thanks to Rod and Ori’s book, plus those various insurgencies since encountered, it all seems so obvious.

My SysAdmin concept is definitely about the multiplication or franchising of authority centers within on-the-ground operations (post-conflict, post-war, counter-insurgency) that the military historically prefers to run in a highly hierarchical manner. But as we know, that can infantilize local capacity – destroy it, actually.

So, absolutely, the military has to embrace a certain “starfish” mentality for the hand-off dynamics to unfold successfully. That doesn’t mean I want the entire US military to go down that route, but the skill set must be developed among those particular forces that get stuck with these ops time and again, and that’s why I originally advocated a certain splitting of the force, between warriors who focus on big wars and those who manage the small conflicts, so the latter would develop and – more important – never discard those skills, which is what we did after Vietnam and are threatening to do again with this new obsession on China and the AirSea Battle Concept.

We’re living through an age of globalization’s globalization – if you will. For decades, the global economy was just the West, but now it’s north, south, east and west – truly global, meaning frontiers are being integrating all over the planet simultaneously. That’s a lot of political-military churn to go along with all that socio-economic change.

So if you want to continue exploiting globalization’s ultimate pacifying effect, you need to aggressively process these many frontiers, settling them down. That’s a huge international project where the US military can only succeed if it enlists as many new allies as possible, and that means going as “starfish” as possible across its relevant organizational edge. To me, that’s the Army, Marines and Special Forces – the core elements of my SysAdmin concept.

To learn more visit wikistrat.com.

Back to top

Book Review

Visual Complexity by Manuel Lima

Author Manuel Lima is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, and was nominated by Creativity magazine as one of the 50 most creative and influential minds of 2009. He is a designer, researcher and founder of VisualComplexity.com, and a Senior UX Design Lead at Microsoft Bing. Lima answers some questions about his insightful book in the following interview:

Q: Your book, Visual Complexity—Mapping Patterns of Information is an amazing compilation of beautiful graphics with essays on how scientists and artists have visually mapped information. The images are very interesting, and compellingly beautiful in some cases, but other than aesthetics, what is the value in creating images that portray the organization of information?

A: Visualization is just one of many tools, albeit an extremely insightful one, that allows us to make sense of patterns, processes, and systems, either natural or man-made. It’s normally through images, maps, diagrams, and various graphical representations that we make sense of the world around us, and this has been the case for millennia. In fact, many advances in civilization can be associated with breakthrough progress in visualization tools.

Q: Your book’s introduction refers to a new network-based outlook on the world that is decentralized and states that this alternative network model is replacing the hierarchical model. Could you elaborate on this concept?

A: Exposed in Chapter Two, “From Trees to Networks,” is the idea that the hierarchical tree model, with all its implied ambition for order, symmetry, and balance, is no longer able to accommodate the inherent complexities of the modern world. As we try to decode our own brain, understand the convolutedness of our urban landscape, or the interdependent reactions of our planet’s ecosystems, the more we realize we are dealing with problems of organized complexity, which cannot and should not be depicted by a simplified, hierarchical tree schema. These new challenges require a new, decentralized, and network-based outlook on the world.

Q: Chapter Two also discusses how the increasing complexity of modern times requires a new way of thinking—network thinking. Maybe this is one of the reasons Rod’s book, The Starfish and the Spider, has had such a profound effect in so many areas, including the U.S. military, private business, and some parts of the U.S. government. Can you tell us how this applies to the planning of cities? You mention in your book the difference in urban layout between pre-Industrial Revolution organic cities like New York and London, compared to the hierarchical centralized organization of model cities such as Brasilia.

A: In Chapter Two I provide several examples that describe this new way of thinking, from how we classify information to how we organize ourselves. The chapter opens with urban planning and a reference to a short essay written by the architect Christopher Alexander in 1965. In “The City is Not a Tree,” Alexander refutes model cities like Brasilia for their hierarchical and centralized organization, but above all, for the absolute disregard for intrinsic human qualities and behaviors.

Driven primarily by major social and economic reforms since the Industrial Revolution, urban planning has been creating a sturdy line between our personal and professional spheres, regarding them as independent and incommunicable modules. This conception of course couldn’t be more different than pre-Industrial Revolution societies—where you literally lived above your workspace—and many organic, naturally evolving cities like London or New York.

Q: What about the world wide web? Is it a decentralized network or a “distributed” model? What’s the difference between these two models?

A: A distributed model is just a type of decentralized system. A “decentralized network” is a figure of speech, as networks are nonhierarchical by definition. The World Wide Web is simply a “web”—as originally coined by Tim Berners Lee—of interlinked hypertext documents, which comprise one of the most sophisticated rhizomatic structures ever created by man.

Q: When discussing the organization of social collaboration, you reference The Starfish and the Spider’s description of the decentralized Apache tribes, and how difficult it was for the centralized Spanish Conquistadors to overcome them. How do you see the leaderless type of social interaction occurring in, and affecting, current and future society?

A : The Starfish and the Spider has been a pivotal book in encapsulating a major shift in modern society, where we appear to realize that social hierarchy is not the norm across societies, nor a necessity or sociological predisposition. As a prime case of a leaderless structure, it is not surprising that the most well-known cases of decentralization are happening on the Web. In fact, the Web might probably be the main driver for this sociological change. As it continues to expand and pervade every level of human activity, the Web also diffuses many of its collaborative social models based on decentralization and democratization, and the effects of this conceptual permeation might influence an everlasting shift in the stratification of society.

Q: At the end of Chapter Two you discuss the importance of network thinking saying, “We act and live in networks, so it makes sense that we start thinking in networks.” What does it mean to think in networks?

A: It means to think in a holistic and systemic way. It means to realize that everything is interconnected and interrelated and interdependent. It means to conceive our planet as a succession of interchanging network systems.

More information on Lima’s book is available at VisualComplexity.com.

Back to top

© 2011 WWW.BECKSTROM.COM

Unsubscribe

|

|